Text by Sarah Morrison of The Independent New Review Magazine

When the British photojournalist Ed Thompson arrived at a snowy Syrian refugee camp in Lebanon last December, he was greeted by a little boy who ran circles around him, making motorbike sounds. Thompson joined in and the subject of his new project was born.

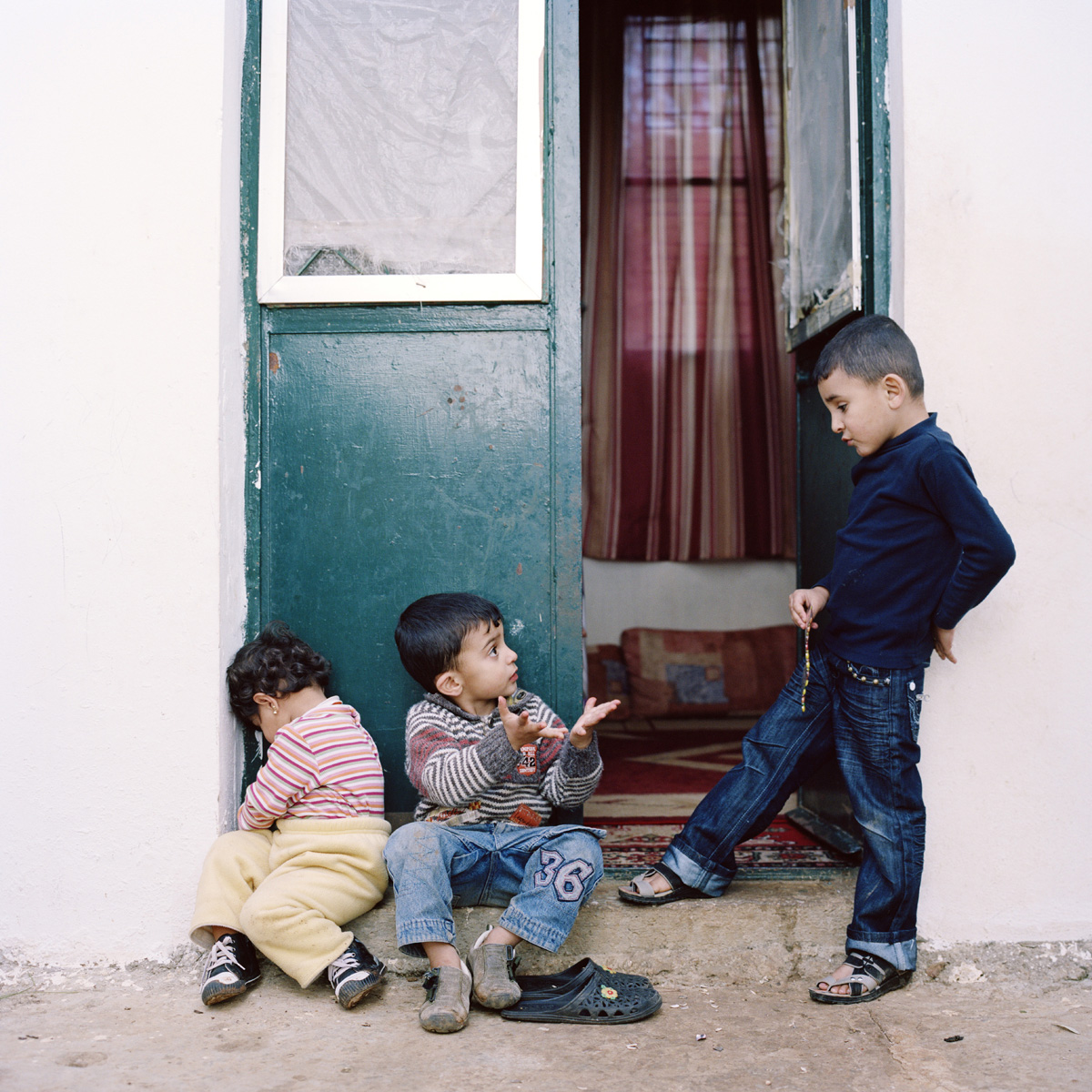

We do not know the name of the boy, or his story. That is partly because Thompson did not make the trip to Lebanon with an NGO or the UN. His visit was instigated by a chance encounter with Sammy Hamze, a 20-year-old Lebanese art student studying in London. They got talking in the pub about the number of Syrians living in Hamze's hometown and, within weeks, were in Lebanon, cameras and notepads in hand. They spent six days in Chhim, western Lebanon, interviewing refugees in camps, those taken in by Lebanese families and those forced to pay steep rent for squalid properties. Keen to break through the political soundbites – lamenting Syria as the "greatest humanitarian tragedy of our times" – Thompson wanted to personalise the crisis and draw attention to two startling statistics: that of the nearly one million (official) Syrian refugees displaced in Lebanon, almost half are children; and around one in five, according to Unicef, are less than five years old.

We have heard the stories. Children at risk of dying from the cold in refugee camps; vulnerable to trafficking; begging on the side of the road; left orphaned and out of school; girls sold into marriage. But what shook Thompson most was that the children, although appearing older than their years, were still so young. "They are innocent, completely innocent," he says now. "One father told me to look at his family; he could barely feed his son. They had been through hell, walked through hell and got to hell. All they want to do is go home."

The conflict that has torn Syria apart has raged for almost three years, left more than 100,000 people dead in its wake and driven nine-and-a-half million from their homes. It took intense political pressure to get the British Government to agree to offer hundreds of the "most needy people" in Syrian refugee camps a home in this country. "We live in the modern age – we can read what's going on in Syria; we've never had more information at our fingertips," says Thompson – "but no one cares."

If anything can break through the apathy, it is his pictures. Lebanon must be close to capacity; a quarter of the country's population are now Syrian refugees, the equivalent of 15 million people arriving on Britain's shores. With ailing infrastructure and its own stretched public services, tensions between the Lebanese and the Syrians are said to be rising. Thompson is so worried about both the security of the people he photographed, and their families back at home, that he does not want to disclose their exact location. Their stories are what he wants told.

Among them is Barja, the mother of two young girls, eight and nine, with disabilities, who fled Syria when her house burnt down. Her husband – the girls' father – was shot and asked Barja to leave him behind. Living in a small rented room in Lebanon for more than a year-and-a-half, she does not know if her partner is alive or dead. "What am I going to do with my life?" she asks. "I barely have money and k I cannot afford to get treatment for the girls. Someone help us please." Then there are the two orphan girls whose parents were shot in Syria. A local sheik took them in. More people live under the mosque; some wounded, others scrabbling for food. Many recount what they lost. Wafaa has been living in a Lebanese family's house for a year-and-a-half with her children. She, too, does not know where her husband is and is worried about her sons. "My sons' futures and education are gone. They were studying medicine and law in Syria. [Now] one works as a janitor in a hospital and he barely gets a good amount of money and my other son works as a labourer. It's sad to see a medical student and a law student doing these jobs; it breaks my heart. We are like everyone else. We are waiting, waiting to go back to Syria."

At a mosque in Chhim

Amer: "One day my brother and I, our wives, the kids, my father, we decided to escape from our town in Homs. We were being attacked from every side, and as we got in a taxi, we got hit on the road. We managed to get out and run but then a second shell fell next to us and I was hit. When I recovered, we [escaped] to Lebanon. We decided to come to Chhim and thanks to the mosque, we have at least shelter. My brother registered us at the United Nations; they helped for two months but after that they stopped. Without surgery, they'll have to cut off [my leg]. Life has come to a stop for us."

Local sheik: "I am in charge of all the refugees here. [These] two [sisters, pictured right] showed up at the town one day; they were in agony, they were helpless. God knows how they found their way from Syria. They told me that their parents got shot, along with everyone from their family, and they escaped. They are so young, it's a miracle they are still alive. I did my best to take them in and help them. They are still in shock and are very depressed; they had nightmares and would run out screaming from the room. I don't know what to do with them except take care of them."

Syrian family living in a small room on the land of a Lebanese family, Chhim Ali: "I brought my family from Syria at the early stages of the war. We are a family of 10. My wife, the children and I live in a little summer house, thanks to the owner, who has been very good. We managed to put a couple of the kids in school. The United Nations are helping us and others as well. People have been generous to us. There are some issues with privacy: for example, if you wanted to have some alone time with your wife, it's a bit hard. We know nothing about our home or relatives in Syria. Originally we are farmers. I'm used to producing food from our land, but due to these hard situations, money does not stay for a long time. Also, I'm providing for my sister's family as well – her husband died. I wish for the best and to go back [to Syria] soon."

Ketermaya refugee camp, Chhim Abu Ahmad: "I escaped from Syria under a hail of bullets, gunfire and bombs; it was horrible. I know nothing about my family, my home or my town. I was one of the first settlers who moved here. I was sleeping in a shack made from a carton and garbage. A few days later another family joined me. We had nothing, no money, no food or water. Nothing until one of the townsmen took pity on us. This piece of land we are on is owned by the landlord Ali. He started helping us, then other refugees started to come here , so we started to set up a camp and establish tents from whatever we could find and what was provided to us here by the people of this town. I have been living here for a year-and-a-half. There are 50 families living here with around 250 people. We have suffered from snakes and scorpions during the summer and now we are suffering from this harsh cold winter. No one is helping us from charities, not even the United Nations. They helped us for two months and then they cut us off."

Syrian refugees living in rented houses, Chhim Yaseen Abdulatif El Dos: "We are living a very hard life; we have nothing. Soon I will have no money to support my family. The water is contaminated. Everything we have here in this room is from the garbage. We had a wonderful life in Syria. Nine people live here in one room and I'm paying $300 rent, and now that winter is here, we are very cold. There's nothing to keep us warm. There's one bathroom open to the kitchen and there is no door. Here's a joke: a rat came in one day and went into the house and he found out that there are Syrian refugees living here so he cursed his head off and left, because we were not Lebanese and had nothing to give him."

Ahmad Taher: "I live here in this cave under this building. Even the poor Lebanese won't live here. It's infested, it's dangerous and I have two children living here. I'm trying my best but conditions are very hard; eight people live in this room. Everything here is killing us slowly. We are poorer than the poor and everything we have here was donated by the townspeople. When we left from Qusair, Syria, we were shot at; my wife broke her leg as well. Somehow I managed to carry her and the kids to safety here. But what can I say? I don't know what to say any more."

If you work for an NGO/Charity and would like to use these images please get in touch.

When the British photojournalist Ed Thompson arrived at a snowy Syrian refugee camp in Lebanon last December, he was greeted by a little boy who ran circles around him, making motorbike sounds. Thompson joined in and the subject of his new project was born.

We do not know the name of the boy, or his story. That is partly because Thompson did not make the trip to Lebanon with an NGO or the UN. His visit was instigated by a chance encounter with Sammy Hamze, a 20-year-old Lebanese art student studying in London. They got talking in the pub about the number of Syrians living in Hamze's hometown and, within weeks, were in Lebanon, cameras and notepads in hand. They spent six days in Chhim, western Lebanon, interviewing refugees in camps, those taken in by Lebanese families and those forced to pay steep rent for squalid properties. Keen to break through the political soundbites – lamenting Syria as the "greatest humanitarian tragedy of our times" – Thompson wanted to personalise the crisis and draw attention to two startling statistics: that of the nearly one million (official) Syrian refugees displaced in Lebanon, almost half are children; and around one in five, according to Unicef, are less than five years old.

We have heard the stories. Children at risk of dying from the cold in refugee camps; vulnerable to trafficking; begging on the side of the road; left orphaned and out of school; girls sold into marriage. But what shook Thompson most was that the children, although appearing older than their years, were still so young. "They are innocent, completely innocent," he says now. "One father told me to look at his family; he could barely feed his son. They had been through hell, walked through hell and got to hell. All they want to do is go home."

The conflict that has torn Syria apart has raged for almost three years, left more than 100,000 people dead in its wake and driven nine-and-a-half million from their homes. It took intense political pressure to get the British Government to agree to offer hundreds of the "most needy people" in Syrian refugee camps a home in this country. "We live in the modern age – we can read what's going on in Syria; we've never had more information at our fingertips," says Thompson – "but no one cares."

If anything can break through the apathy, it is his pictures. Lebanon must be close to capacity; a quarter of the country's population are now Syrian refugees, the equivalent of 15 million people arriving on Britain's shores. With ailing infrastructure and its own stretched public services, tensions between the Lebanese and the Syrians are said to be rising. Thompson is so worried about both the security of the people he photographed, and their families back at home, that he does not want to disclose their exact location. Their stories are what he wants told.

Among them is Barja, the mother of two young girls, eight and nine, with disabilities, who fled Syria when her house burnt down. Her husband – the girls' father – was shot and asked Barja to leave him behind. Living in a small rented room in Lebanon for more than a year-and-a-half, she does not know if her partner is alive or dead. "What am I going to do with my life?" she asks. "I barely have money and k I cannot afford to get treatment for the girls. Someone help us please." Then there are the two orphan girls whose parents were shot in Syria. A local sheik took them in. More people live under the mosque; some wounded, others scrabbling for food. Many recount what they lost. Wafaa has been living in a Lebanese family's house for a year-and-a-half with her children. She, too, does not know where her husband is and is worried about her sons. "My sons' futures and education are gone. They were studying medicine and law in Syria. [Now] one works as a janitor in a hospital and he barely gets a good amount of money and my other son works as a labourer. It's sad to see a medical student and a law student doing these jobs; it breaks my heart. We are like everyone else. We are waiting, waiting to go back to Syria."

At a mosque in Chhim

Amer: "One day my brother and I, our wives, the kids, my father, we decided to escape from our town in Homs. We were being attacked from every side, and as we got in a taxi, we got hit on the road. We managed to get out and run but then a second shell fell next to us and I was hit. When I recovered, we [escaped] to Lebanon. We decided to come to Chhim and thanks to the mosque, we have at least shelter. My brother registered us at the United Nations; they helped for two months but after that they stopped. Without surgery, they'll have to cut off [my leg]. Life has come to a stop for us."

Local sheik: "I am in charge of all the refugees here. [These] two [sisters, pictured right] showed up at the town one day; they were in agony, they were helpless. God knows how they found their way from Syria. They told me that their parents got shot, along with everyone from their family, and they escaped. They are so young, it's a miracle they are still alive. I did my best to take them in and help them. They are still in shock and are very depressed; they had nightmares and would run out screaming from the room. I don't know what to do with them except take care of them."

Syrian family living in a small room on the land of a Lebanese family, Chhim Ali: "I brought my family from Syria at the early stages of the war. We are a family of 10. My wife, the children and I live in a little summer house, thanks to the owner, who has been very good. We managed to put a couple of the kids in school. The United Nations are helping us and others as well. People have been generous to us. There are some issues with privacy: for example, if you wanted to have some alone time with your wife, it's a bit hard. We know nothing about our home or relatives in Syria. Originally we are farmers. I'm used to producing food from our land, but due to these hard situations, money does not stay for a long time. Also, I'm providing for my sister's family as well – her husband died. I wish for the best and to go back [to Syria] soon."

Ketermaya refugee camp, Chhim Abu Ahmad: "I escaped from Syria under a hail of bullets, gunfire and bombs; it was horrible. I know nothing about my family, my home or my town. I was one of the first settlers who moved here. I was sleeping in a shack made from a carton and garbage. A few days later another family joined me. We had nothing, no money, no food or water. Nothing until one of the townsmen took pity on us. This piece of land we are on is owned by the landlord Ali. He started helping us, then other refugees started to come here , so we started to set up a camp and establish tents from whatever we could find and what was provided to us here by the people of this town. I have been living here for a year-and-a-half. There are 50 families living here with around 250 people. We have suffered from snakes and scorpions during the summer and now we are suffering from this harsh cold winter. No one is helping us from charities, not even the United Nations. They helped us for two months and then they cut us off."

Syrian refugees living in rented houses, Chhim Yaseen Abdulatif El Dos: "We are living a very hard life; we have nothing. Soon I will have no money to support my family. The water is contaminated. Everything we have here in this room is from the garbage. We had a wonderful life in Syria. Nine people live here in one room and I'm paying $300 rent, and now that winter is here, we are very cold. There's nothing to keep us warm. There's one bathroom open to the kitchen and there is no door. Here's a joke: a rat came in one day and went into the house and he found out that there are Syrian refugees living here so he cursed his head off and left, because we were not Lebanese and had nothing to give him."

Ahmad Taher: "I live here in this cave under this building. Even the poor Lebanese won't live here. It's infested, it's dangerous and I have two children living here. I'm trying my best but conditions are very hard; eight people live in this room. Everything here is killing us slowly. We are poorer than the poor and everything we have here was donated by the townspeople. When we left from Qusair, Syria, we were shot at; my wife broke her leg as well. Somehow I managed to carry her and the kids to safety here. But what can I say? I don't know what to say any more."

If you work for an NGO/Charity and would like to use these images please get in touch.